Do you remember three-dimensional chess in the old Star Trek? That’s an image that kept coming back to me as I tried to pick apart this solo, along with a nagging question: What would this performance - note-for-note, the exact thing, played by the same guys - what would it’ve sounded like recorded and mixed on today’s equipment? And this: Jazz today operates in a world where we can make a “perfect” recording, fixing after the fact anything that might be perceived as a mistake. More and more young jazz players are able to fulfill the expectation (largely self-imposed) of intellectual rigor. Has the music lost complexity in the bargain?

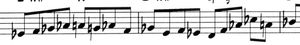

We'll look at Brown’s solo first, then consider the contributions of two of his fellow mages, George Morrow and Richie Powell. The whole solo appears below.

Clifford Brown and company could definitely play over any changes they wanted to, but it’s hard to imagine many things in music more boring than a whole band “playing over the changes.” (Ask me how I know this!) What are “the changes” anyway? The written chords of Daaoud as seen here, are a surface representation. The play of harmonic motion against the gravity of the tonic leaves a broad mental impression. This “psychological imprint” (to use Saussure’s phrase) is necessarily less detailed than the actual written harmony. A set of changes is one way of eliciting a particular impression of motion. So much of what is interesting in this solo is not how Brownie plays over the changes. Rather, it is his shifting relationship to them which gives his solo so much of its depth and richness.

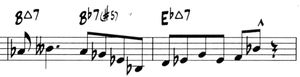

Brown alternates between three harmonic/structural levels in his two choruses: the “home key” of Eb minor/major, which may be considered the “deepest” level, and the one which influences all the others; the key of the moment; and the chord of the moment. There are a few passages here which, on paper, might be seen as a “mistake,” unless viewed in relation to one or the other of these levels. For example, the line

is obviously a line in Eb minor. Yet though it clashes visually with the written chord changes in the second bar, nobody hears this as a “mistake” or a lapse. Notice also the way Brown all but ignores V - I cadences when they occur in the home key of Eb min/maj.

nobody hears this as a “mistake” or a lapse. Notice also the way Brown all but ignores V - I cadences when they occur in the home key of Eb min/maj.

The different levels of a tune are simultaneously compatible. For students of jazz, gaining some facility at playing in the deepest levels, that is, playing in one key, should be a prerequisite to trying to negotiate harmonic changes.

When Brown plays “chord-specifically,” he may outline a chord or play a scale line that reflects a chord substitution. Chord outlines usually begin with approach notes, with the fifth as a frequent insertion point into the chord.

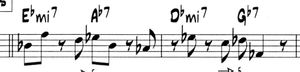

Having the rhythm section accurately mark the harmony gives the soloist the freedom to attend to it, or not. However, if you listen to the counter melody generated by Powell’s right hand, you can hear that he keeps his soloist firmly grounded throughout in the tonality of Eb. Bassist George Morrow plays to a seemingly simpler set of changes, showing less harmonic motion than Powell’s piano part. Notice especially the almost exclusive use of a Bb UNDER Powell’s Bmaj7 chords. Again, it only looks like a mistake.

Here we have three great players functioning simultaneously at different structural levels, harmonic rhythms, and interpretations of the harmony, gloriously coexisting: great players making art. And in so doing, they reflect and compliment the human ear, in all its fascinating complexity.